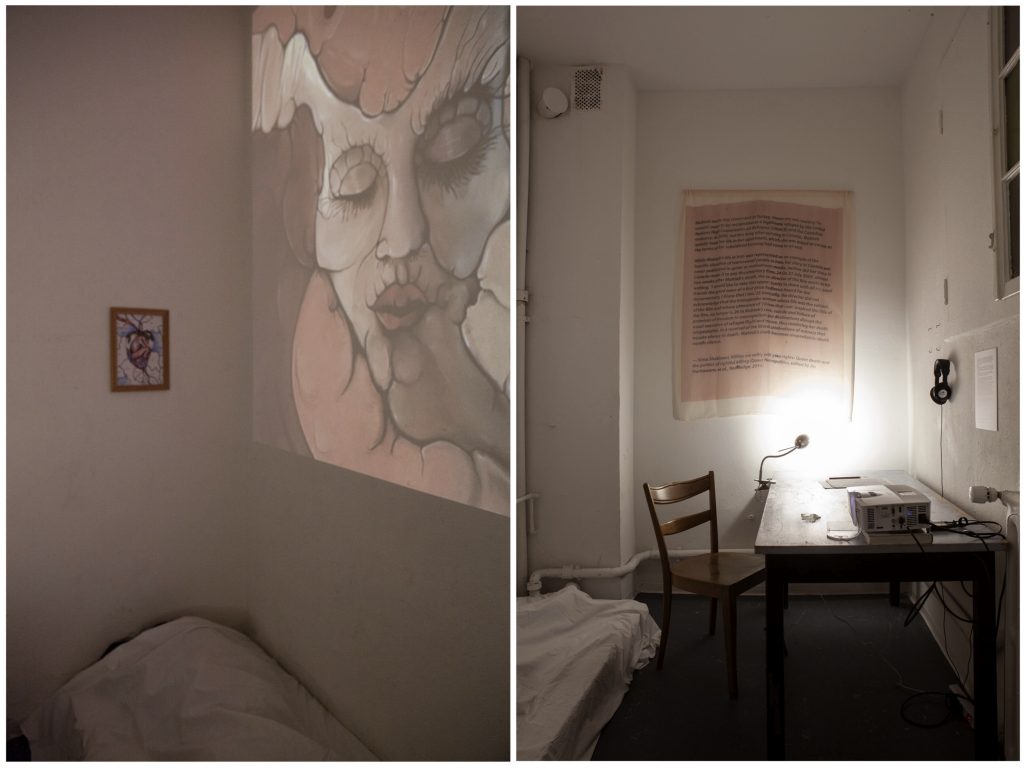

A room of her own (installation)

View of the room

Here you can watch the animation projected on the wall, also the Farsi translation

نسخه فارسی این نوشته را اینجا مطالعه کنید

A Room of Her Own

By kamran Behrouz

A room of her own as part of the corpoanarchy, is a tribute to the unspeakable death of queer and trans people who silently disappear from the collective memory of queer culture. When I read mahtab’s case [1] for the first time, it immediately reminded me of Virginia Woolf’s essay “a room of one’s own”[2]. In Mahtab’s case, it seems comfort has been so disturbed, that the death became the comfort itself. Death as the only room of one’s own.

Archive:

In 2016 while I was researching through the archives of Iran human rights documentation center, looking for the cases and testimonies of trans and queer refugees, as well as the rates of suicide amongst these groups, I accidentally came across Mahtab’s case, which led me directly to Sima Shakhsari‘s work and their crucial chapter: killing me softly with your rights. [3]

The story of Mahtab or Sayeh [4] underlies an unspeakable death, which Shakhsari analyzes in depth, and sadly, this story is not the only one: there are several similar cases regarding to the necropolitics of queer displaced bodies.[5]

Iran has a peculiar and paradoxical history of gender and sexuality. “Some of the conceptual distinctions among gender, sex, and sexuality within the Anglo-American context, including the distinction sometimes made between transgender and transsexual (based on surgical modifications to the body), have been shaped over the past decades by the identity politics of gender and sexuality as well as queer activism and queer critical theory. Transsexuality in Iran has not been shaped by such developments” [6]. Contemporary narratives affirm that trans people are legally accepted as “correction cases”, and in fact they need to go through long and absurd interviews and examinations called “diagnostic test” in order to be separated from Homosexuals (on the contrary homosexuality considered deviation and a highly discriminated practice).

Sometimes those interviews are consisted of utterly absurd and gender normative questions such as: “Do you squeeze your toothpaste tube in the middle or from the bottom up?” [7] Some of these random questions determine one’s gender identity as well as the fate of their body. Some of these random questions determine which hormones belong to which bodies and which bodies are illegal or degraded.

Surprisingly in such controversial country, after this process, trans people are legally accepted and legitimate to go through transition, hormone therapy and surgery and even get a new identification card or passport, however, transition in Iran is not a matter of choice but rather a normalization process: an obligatory rule for transgender people to turn into ‘corrected bodies’. So what we have as an archive of trans people in Iran is limited only to those who accepted this process and went through it. What have never been documented or simply erased is the history of those bodies who refused or never came out as a trans person.

If it is Biopolitics, how should we map it? A condition that forces trans people to either transition or leave and deal with other forms of necropolitics, biopolitics or border policies? a condition designed to make you depressed while suspends you within the necropolitical borders? A presumably depressive condition and ironically, the prescribed remedy made by pharmaceutical industries, is a substance like antidepressant which its side effect is “suicidal thoughts”. [8]

‘Corpoanarchy’ as a series of visual and performative acts, suggest a molecular resistance in such cases by rejecting the forces of substances as a molecular disobedience! Not only hormones in unnecessary situations but also other substances such as several antidepressants which according to their own guideline on the packages: “suicidal thoughts might be the side effect of this medication”

[1] “Mahtab was waiting for several years to be recognized as a legitimate refugee by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) and the Canadian embassy. In 2008, not too long after arriving in Canada, Mahtab quietly took her life in her apartment, which she was asked to vacate as the terms of her subsidized housing had come to an end”

— Sima Shakhsari, killing me softly with your Rights – Queer Necropolitics, edited by Jin Haritaworn, et al., Routledge, 2014

[2] A room of one’s own,(first published in September 1929), Virginia Woolf, collector’s library, London, 2013

[3] The transgender studies reader Vol.2 edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle, Routledge, New York, 2006-2013

[4] In most of the articles, names have been changed due to privacy protection.

[5] https://iranhrdc.org/in-memory-of-marjan-ahouraee-an-iranian-transsexual-refugee/

[6] Professing selves: Transsexuality and same sex desire in contemporary Iran, Afsaneh Najmabadi, Duke university press, Durham, 2014, pp. 8

[7] Professing selves: Transsexuality and same sex desire in contemporary Iran, Afsaneh Najmabadi, Duke university press, Durham, 2014, pp. 30

“The presumption is that females are neat and press from the bottom up; males just squeeze the toothpaste tube randomly, usually from the middle” pp.261

[8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC427603/#!po=3.57143

Silk screen and digital print on textile

Printed text on the curtain:

“…Mahtab made this statement in Turkey, where she was waiting for several years to be recognized as a legitimate refugee by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) and the Canadian embassy. In 2008, not too long after arriving in Canada, Mahtab quietly took her life in her apartment, which she was asked to vacate as the terms of her subsidized housing had come to an end.”

While Mahtab’s life in Iran was represented as an example of the horrific situation of transsexual people in Iran, her story in Canada was never publicized in queer or mainstream media, neither did her story in Canada make it to any documentary films. On 31 July 2008, almost two weeks after Mahtab’s death, the co-director of the film wrote in his weblog, ‘I would like to take this oppor- tunity to share with all my good friends the good news of a first prize Audience Award for the documentary, I Know that I Am.’ Ironically, the director did not acknowledge that the transgender woman whose life was the subject of the film and whose utterance of ‘I know that I am’ inspired the title of the film, no longer is. In Mahtab’s case, suicide and failure of promises of freedom in cosmopolitan gay destinations disrupt the usual narrative of refugee flight and rescue, thus rendering her death unspeakable. In a reversal of the liberal celebrations of outness that equate silence to death, Mahtab’s death becomes unspeakable: death equals silence”

— Sima shakhsari, (Killing me softly with your rights, Queer death and the politics of rightful killing), Queer Necropolitics, edited by Jin Haritaworn, et al., Routledge, 2014

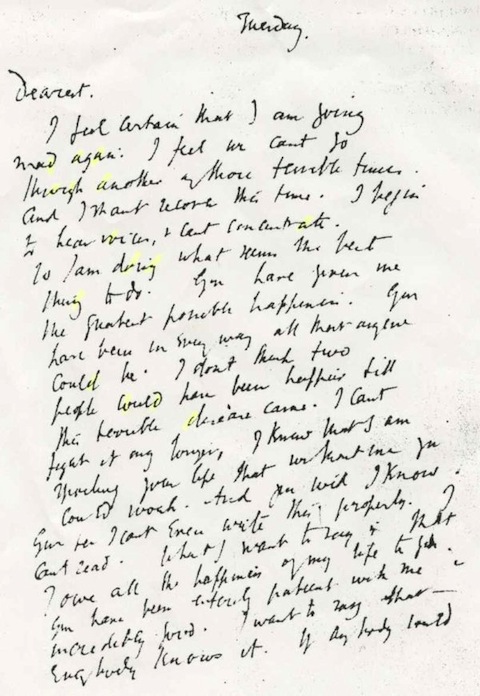

Image: Virginia Woolf’s handwritten suicide note

“So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters; and whether it matters for ages or only for hours, nobody can say.”

—A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf, chapter 6

In this lecture: (Queer Necropolitics), Shakhsari unfold their ethnographical research related to queer life and death, and propose a view to rethink the notion of rights.

(The idea of virtual lecture came up after we realized it is not possible for Sima Shakhsari to travel to Zurich in order to give a lecture within the exhibition space. Even though they have “legal permanent residence” status, but because of uncertainty of how the ban would affect green card holders, they afraid to leave the U.S.)